I was recognized for my care of these civilian workers and my role in assembling and coordinating the specialized care team – and given the Halliburton Hometown Hero honor.

Civilian workers, soldiers’wounds / Led to a combat zone by hefty wages and ambitions,nonmilitary personnel are becoming casualties of war

IRAQ’S OTHER TOLL / Civilian workers, soldiers’wounds / Led to a combat zone by hefty wages and ambitions,nonmilitary personnel are becoming casualties of war

By Mary Ann Fergus

Copyright 2004 Houston Chronicle

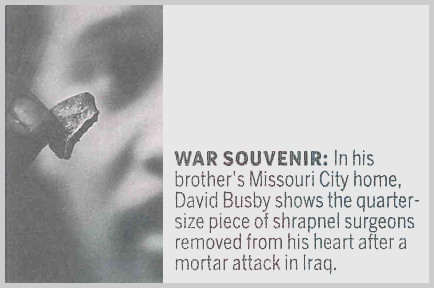

A footlong scar runs down David Busby’s chest where a surgeon drew a quarter-size piece of shrapnel from his heart. The metal sits in a plastic cup on his dresser, a civilian’s souvenir of war.

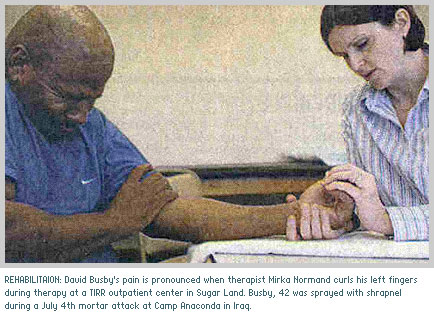

Busby has plenty of other reminders of the Fourth of July mortar attack in Iraq. He can’t raise his left foot and wears a brace up to his knee. His left fingers can’t touch his palm.

As thousands of tiny bits of shrapnel rise to his skin’s surface, like splinters working their way out, Busby plucks them with a tweezer. He takes Vicodin for pain, pops Ambien to sleep. Crowds and loud noises panic the 42-year-old from Missouri City.

The pain, sleeplessness and panic are not what this outgoing man with soft eyes bargained for in January when he took a job for KBR, Halliburton Co.’s subsidiary, in Iraq.

“It wasn’t that they didn’t tell us the risks,” Busby said after a recent physical therapy session. “But then again, you forget very quickly when the large paychecks come in.”

As the Defense Department contracts out jobs traditionally done by military personnel, a subculture is growing: civilians with the kind of war-related experiences normally only felt by soldiers.

At least 170 contract workers – 52 of them from Halliburton – have died since U.S. troops invaded Iraq in March 2003, according to Iraq Coalition Casualty Count, a Web site that tracks coalition deaths. The Pentagon doesn’t track the number of civilians working in Iraq or their injuries.

Houston is home to Halliburton, KBR and, therefore, the civilian war labor movement. Each week, the company sends 350 to 400 workers to Iraq.

The most severely injured are likely to return to Houston for treatment at Houston Methodist Hospital, which has an informal arrangement with the company.

Halliburton is the largest U.S. contractor in Iraq and Afghanistan, with more than 30,000 workers and government contracts worth at least $11.4 billion to provide logistics and restore the country’s oil infrastructure.

As the conflict drags on, Halliburton has become a presidential campaign issue. Democrats question the Bush administration’s relationship with the company, which Vice President Dick Cheney once led as chief executive. The Pentagon has investigated whether the company overcharged the government; the Army has since backed off its threat to withhold payments on food and fuel bills.

The 700 to 800 civilian workers who have been injured to varying degrees remain virtually anonymous. Unlike for soldiers, there are no cameras or crowds offering a hero’s welcome when they return.

Unarmed in harm’s way

Chris Caldwell, a buyer for KBR, had just walked onto his balcony at the Palestine Hotel in Baghdad one morning last November to smoke a cigarette when rockets hit the floor above him.

Shrapnel sprayed his body and punctured his brain. The 27-year-old has endured nine surgeries, leaving stitches across and down the left side of his shaved head.

As Caldwell underwent daily therapy this spring and summer, Linda Lane sat beside her husband, Reggie, on the third-floor brain-injury unit in The Institute for Rehabilitation and Research in Houston and tried to coax him out of a state of aphasia. Reggie Lane can see and hear, but he can’t make sense of the sights and sounds around him.

A Vietnam veteran from Montana, Lane lost his right forearm and suffered other injuries when a grenade hit his KBR truck in Iraq in April. Later he developed a blood clot that deprived him of oxygen.

For much of the summer, Lane sat in a wheelchair or his bed at TIRR, his blue eyes unfocused or closed, his mouth cast downward. He wore a diaper, a feeding tube and a trachea tube.

Linda Lane alternated between hope and despair.

“He is alive, but he’s not… It’s like death laughing at me,” Lane says. “I have walked in his room, and I have gone to my knees.”

High reward, high risk

Busby, Caldwell and Lane all took their jobs for the money and to help make long-range plans come true. They shared varying degrees of patriotism as well.

Salaries range from about $60,000 to, in rare cases, $200,000. Drivers like Lane earn about $80,000, income-tax-free.

The contract tripled Lane’s income. The men worked seven days a week, 12 hours a day, in 120-degree heat.

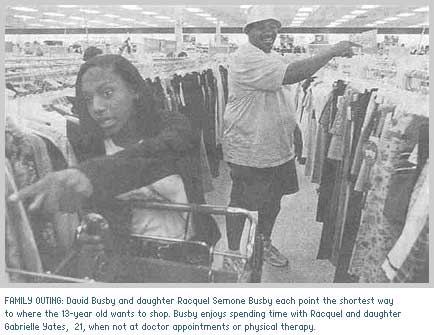

Busby, a divorced father of two, saw the KBR job as a chance to earn more money. He also worked for the company in Bosnia in 1999.

Caldwell was a National Guardsman already working for KBR in Houston and said he believed a post in Iraq would help him advance.

Lane, 55, planned to build a home in Montana, where he and his wife could relax.

But first they had to survive Iraq.

Security workers, then truck drivers, are most common among the slain civilians, according to the Iraq Coalition Casualty Count site. Drivers can face gunfire, mortar attacks, missiles and car bombs. They start each delivery run with a prayer.

But it was April 9, when seven KBR contractors – including Tommy Hamill of Macon, Miss. – were kidnapped in an ambush, that brought the danger into focus.

Hamill, a dairy farmer turned truck driver, gained a measure of fame after he escaped from his captors. Four of the other men were later found dead; two remain missing.

The day before, Lane had talked with KBR co-worker Jason Hurd of Houston about the growing violence.

They pledged to stay and support each other. Hurd lived up to that promise the next day when their convoy was attacked. Speeding from the gunfire, he noticed a truck moving slowly at the edge of the road.

Lane was at the wheel. His right forearm was lost, and he’d been shot in his left arm. Blood had splattered all over the truck.

“It was like a slaughterhouse,” Hurd said.

Hurd and two others pulled the 6-foot-6, 260-pound Lane from the truck.

“He was our big dad,” Hurd said.

Hurd visited Lane at TIRR in July and found him in bed, his legs covered with protective foam because he often thrashed wildly. Hurd left the hospital in tears.

He returned to Iraq, but loved ones were concerned.

Two weeks later, Hurd broke his one-year contract with KBR. He still has mixed emotions.

“I’m going, ‘You know what, I don’t want to let these thugs win,’ ” Hurd said. “I just felt my nine lives were running out.”

Fear and pride

Jennifer Caldwell was a University of Houston marketing major when she got a 2 a.m. phone call from a KBR employee who said her husband had been injured but was OK.

“If Chris was OK, he’d be calling me,” she said.

When Jennifer saw her husband days later at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C., she barely recognized him. The left side of his head and face was swollen. Virtually no part of his body was left unharmed.

Thirteen days after his attack, Caldwell awoke at Memorial Hermann Hospital speaking in the gibberish of a brain-injured man.

At 25, Jennifer Caldwell has changed her husband’s diapers and cleaned his wounds – and cared for sons Michael, 4, and Brennan, 18 months.

“I don’t fear old age anymore,” said Jennifer, who now works in government operations at KBR’s Houston office. “I’ve done things most wives don’t have to do until the geriatric years.”

Chris Caldwell left TIRR in December, then went through intensive outpatient therapy for several months.

The first time he was asked to read, he thought he was looking at Spanish. When he learned it was English, he wept. He had to relearn the alphabet, then words. A simple sentence could take five minutes to read. He can now read and write again and is working on increasing his speed.

Days before he was injured, Chris Caldwell had talked excitedly with Jennifer about KBR’s work in Iraq and the potential for democracy. He feels the same way today.

“I’m proud of this company, despite the fact that I got blasted,” Caldwell said.

While Chris Caldwell’s life moves forward, Reggie Lane’s seems frozen in time.

In late April, Lane arrived at Houston Methodist Hospital.

About a month into Lane’s treatment, neurologist Steven Lovitt told Linda Lane that her husband would likely remain in a vegetative state. Linda choked back tears.

“My husband is going to get better, and when he does, I’ll have him call you,” she told him.

“I’ll be waiting for his call,” Lovitt replied.

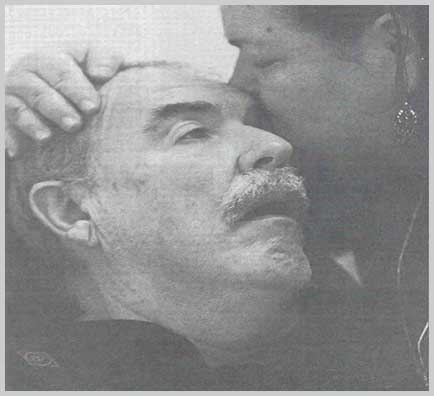

In addition to conventional therapy at TIRR, Linda Lane hired Houston shaman Eric Davis for daily energy therapy.

Davis placed his hands on Lane’s head, legs and arms while talking to him.

He often awakened Lane to the point that he silently stared at his wife, Davis, and others in the room.

In August, it seemed Lane was improving. One day he wept for an hour in his wife’s arms. The next day he kicked his right foot and laughed. He was taken off his trachea tube. Staff at TIRR noticed him following their voices.

But his progress since then has been slow. Linda fights to stay positive but has no regrets.

“He would go again, and I would send him again,” she said. “I don’t hold (KBR) responsible. He had protection over there. … They drove into an ambush. It was just destiny; it was just living life.”

Unfinished business

In April, three wounded KBR drivers, including Lane, needed treatment that hospitals in their hometowns couldn’t offer.

Halliburton officials turned to orthopedic surgeon Dr. Evan Collins at Houston Methodist Hospital in Houston, and he put together a team of about 10 specialists. They’ve treated about 20 wounded workers, mostly men, with broken bones and internal injuries.

“What’s interesting and shocking,” Collins said, “is that as hurt as they are and as devastating as many of these injuries are, it’s, `When can I get back (to Iraq)?’ They feel like they’re doing a job that’s … important.”

Busby, sprayed with shrapnel from a mortar round as he was standing inside Camp Anaconda, has been tough on himself throughout his recovery.

He was determined not to use a bedpan. He spent two weeks learning to lace shoes with fingers that could barely bend. He promised himself he’d walk without a cane by his 42nd birthday. He did.

Outside the hospital, Busby felt vulnerable. At night he had odd dreams and awoke at 4 a.m. He received a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder and sees a psychiatrist.

Until recently, he spent three days a week in physical therapy for his leg and hand. Busby recently stopped hand therapy because he found the pain excruciating. He may need additional surgeries on his hand and leg.

He ponders his future – work or school – and tries to stay positive.

“Yes, I got blown up in Iraq,” Busby joked, “but the good news is that I lost 42 pounds in 10 days.”

In September, Caldwell passed his driver’s license exam. He hopes to work on job skills and return to KBR.

Dreams for the Lanes’ home in Montana are on hold. Reggie is still at TIRR, but Linda plans to move him to a nursing home in his hometown of Grants Pass, Ore., to be near family.

Jason Hurd now drives trucks during the week and attends real-estate school on weekends. He hopes to be selling homes in The Woodlands, a world away from mortar and missiles. “I thank the Lord every day that I’m able to have my hands, my legs,” Hurd said. “Every day.”

…

FOR THE INJURED:

The benefits for the injured workers:

The benefits: Halliburton or KBR workers injured in Iraq get weekly compensation in lieu of salary until they can return to work; their medical bills are covered. Compensation for total disability is two-thirds of the worker’s average weekly earnings, up to about $1,000 per week.

Who pays: At KBR, benefits are paid by AIG Worldsource, the company’s insurance carrier.

The law: Injured workers’ benefits are paid pursuant to the Defense Base Act, an extension of the Federal Workers Compensation Act.

FIRMS INVOLVED

U.S. firms with largest contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan:

Halliburton, headquartered in Houston. Providing logistics and infrastructure rebuilding. Contracts: at least $11.4 billion.

Parsons Corp. of Pasadena Calif. A design and engineering firm. Contracts: $5.3 billion.

Fluor Corp. of Aliso Viejo, Calif. One of the world’s largest publicly traded construction companies. Contracts: $3.8 billion.

Washington Group International of Boise, Idaho. A construction and engineering firm. Contracts: $3.1 billion.

Shaw Group/Shaw E&I of Baton Rouge, La., providing environmental and infrastructure services. Contracts: $3.1 billion.